How to Understand and Heal Sexual Pain

There has been a long-standing tradition in the history of pain medicine that separates mind and body. Pain is described as either a physical sensation and a sign of bodily damage in need of repair or psychological in nature, not connected to any physiological cause and an expression of psychological suffering, grief, trauma etc. Pain science has evolved a lot in the last 30 or so years and we know pain is more complex than this, even with pain that is connected to a body part.

Pain is more like a perception of the state of our overall mind-body system; a summation and interpretation of all of the available information about what is happening for us in a given moment, including what resources are available, the meaning of what is happening for us, contextual environmental factors, previous experience etc, and the result is an experience that drives adaptive or coping behaviours.

What I hope this blog can provide is an introduction to how pain science can help us understand the experience of sexual pain, how it can develop, and provide hope for treatment approaches that can ultimately support us in healing our relationship with our bodies, sexual identity and intimacy.

What is pain?

Pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” Potential is an important word here as it can be experienced in anticipation of danger; a prediction. It is designed to intrude on and capture our attention as we may need to respond quickly to protect ourselves and promote recovery.

Our nervous systems are constantly trying to maintain a process called homeostasis; that is, being able to maintain the internal stability of systems, such as immune, digestive or respiratory functions, while adapting to the demands of a changing external environment. It has to filter through so much information to do so and decide what is important to maintain this stability and what is background noise to ignore. For example, you don’t usually think about your breathing until it becomes a concern. You may be familiar with the five senses but it has been argued we actually have ten. These include balance and movement, pressure, breathing, fatigue, pain, itch, temperature and appetite, each designed to provide important information to the brain, to motivate action in some way to support a return to homeostasis. Here are some examples: The feeling of imbalance urges us to find stability again to avoid falling and potential danger. There are limits to our ability to regulate our internal temperature and so we need sensations that motivate us to protect ourselves from cold and heat by taking off a coat. Pain is alarming and is designed to intrude into our attention to promote escape, repair, learning or to communicate a need for care and support from others.

Pain is also not static, but its meaning can change depending on the context. Pain can be perceived differently for example if it is seen as a part of a valued goal, a rite of passage, a religious/spiritual experience or as part of a kink. Pain in these instances is known and understood. Pain without a clear meaning or understanding can be challenging to cope with as it intensifies our worry and search for a reason and solution, including feeling that something is wrong, broken and in need of repair.

How does pain work? - Specialised nerves called nociceptors detect extremes in temperature and pressure and injury-related chemicals all over the body. When enough information is detected, signals are sent to the spinal cord and onto the brain. The brain weighs up this information against a range of contextual factors and if it feels it is adaptive to move into a protective response, pain will be experienced. As pain is distressing, it motivates us to act quickly to protect ourselves.

Pain may not always be useful to our system though. If nociceptors are active repeatedly for a sustained period of time, the brain may learn to pay more attention to those nerves and increase the sensitivity of those nerves to be able to better protect the body. This means less input is needed to provoke a strong pain response over time or the signal to the brain becomes clearer and louder. This is called central sensitisation and is often experienced with chronic or persistent pain where pain outlasts any actual damage that may have been sustained beyond healing time. Our brains are great at learning and adapting but it can also learn some unhelpful habits. Our brains can get better and better at feeling pain and pain can become chronic.

Pain is not always an accurate reflection of what is happening in a body part. For example, phantom limb sensations and pain exist without the nerves that would be responsible for sensation in the missing limb. Pain in this instance demonstrates the critical role of the brain in our experience of pain. This pain is absolutely real, however it is no longer a helpful experience for us. All pain is processed by the brain which can decide, outside of conscious awareness, where, when and how much pain to experience.

There is also a famous story of a builder who presented to the emergency department in excruciating pain. He had jumped onto a 15 inch nail and his foot was in immediate pain. When doctors removed the boot, they were shocked as the nail had passed between two toes. Once this was understood, the pain disappeared, it was no longer adaptive to experience. His pain was very real as it matched his understanding of what was happening. Our beliefs about pain, personality, emotional and psychological state and expectations about treatment can also influence how much pain is experienced, for example how much control we perceive ourselves to have over the pain and how supported we feel regarding our pain can influence how strong that pain is perceived to be. For the builder, the context said that terrible damage must have occurred. How we interpret pain will lead to very different experiences and behaviours.

To treat pain conditions, we need to understand why the brain has gotten so adept at learning to experience pain.

What is sexual pain (Dyspareunia)?

Dyspareunia is the term used to describe painful sexual intercourse due to medical or psychological causes. The pain can primarily be on the external surface of the genitalia, or deeper in the pelvis. Pain with sex can also occur for people with penises, however most people presenting for support tend to be those with vulva’s and reflective of current research, which will be the focus for the rest of the blog.

Sexual pain can be primary - sex has always been painful, or secondary - sex has become painful after a period of this not being the case. It can be caused by many factors including recurrent UTIs, vulval or vaginal skin disorders, tight or overactive pelvic floor muscles (Vaginismus), as a response to fear and anxiety, following traumatic childbirth or surgery, previous trauma including sexual trauma… The type of pain and where the pain is experienced can also vary from tight, burning or aching pains to pain around the entrance to the vagina to the lower abdomen and vulva.

Amongst the clients we see at SHIPS, there are two main conditions that contribute to sexual pain, Vaginismus and Vulvodynia. Vaginismus involves the involuntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles that makes any sexual activity that involves penetration painful or impossible. Vulvodynia is a persistent pain disorder which involves highly sensitised nerve endings in and around the vulva described as a burning, stinging or irritation. The pain may be constant or come and go. Sensations in the nerves are perceived by the brain as abnormal and over time result in heightened sensitivity and prioritisation of messages from the area to the brain (sensitisation).

How can pain science help us understand sexual pain?

As we have seen, meaning is incredibly important to the experience of pain, this is also true for sexual pain. Both culturally and in medicine we have often looked at our bodies in the same way as we look at machines: Is it working? Is it broken and in need of repair or fixing? We have systems devoted to classifying what is normal and abnormal and moralistically we assess things in absolute terms; right/wrong, good/bad, normal/abnormal. We actively look for this information around us when we make comparisons to our friends, to social media, to cultural norms about how to be and how to live our lives. With sexual pain too, it is not uncommon that I hear the body as a machine metaphor when clients say my body doesn’t work the way it should, it is broken, sex should be easy, anyone can and should do it etc… Pain from this lens is a sign of a broken and abnormal system. It may also be understandable, if imperfect, in light of what we know about how pain works.

There may also be positive associations about sex, for example, it may be something you want to be able to share with a partner, it may represent a love language or a way of creating connection and intimacy. However, if there is more credible evidence towards threat than safety then a protective response will tend to be prioritised. Other forms of protection may also be occurring apart from pain including flight/avoidance; perhaps you may be vigilant to any potential signs your brain has related to sex as it may predict future pain.

Safety and pain - what contextual factors contribute to the development and maintenance of sexual pain?

Trauma including sexual, attachment, medical etc and especially traumas that have made you feel unsafe or marginalised in your bodily experience or in relation to getting closer to others.

You grew up with messages where sex and sexual expression were seen as shameful, bad, something to be feared.

Early life experiences where your core emotional and/or physical needs were not consistently met and together with temperament and subsequent life experiences you have schemas which impact how you approach intimacy and sex. For example, if love and attention was conditional on acting in certain ways growing up you might learn that in relationships you need to seek the approval of others to avoid abandonment. This might mean you struggle to prioritise your sexual needs and communicate them to a partner and this tension between the need for approval and feeling a lack of pleasure is distressing, triggers a nervous system response and leads to your pelvic floor tightening.

You have a challenging or negative relationship to your body, for example, body image concerns, body dysmorphia, the body is a reminder of trauma and abuse…, and it feels confronting or threatening to be aware of and connected to your body including during sexual experiences.

You are not attuned to or aware of your needs and preferences and/or struggle to communicate this to a sexual partner.

Due to evolution and prior learnt experiences we instinctively link pain with damage and danger. This can reinforce worry that something is wrong and contribute to the maintenance of sexual pain.

Once we experience pain during sex, our brain may associate the two and begin to anticipate pain in advance. We may experience fear which reinforces the feeling of there being something wrong, which escalates our fear, further reinforces that sense of danger and forms a vicious self-perpetuating loop. It might also make us avoid sex which may be associated with some short-term relief but ends up reinforcing a sense of danger to avoid feeling fear and pain. This is a conditioned response which is normally helpful, we can learn not to eat something if it makes us feel sick, but with painful sex it becomes an impediment to feeling a positive relationship with sex.

If you don’t feel believed or supported by healthcare providers who may dismiss or minimise your feelings. Do we feel believed and supported by partners, family and friends?

Concurrent concerns in an intimate relationship including difficulties with trust, disconnection, lack of communication regarding sex and needs, navigating a significant change in the relationship e.g. following the birth of a child.

The biomedical model tries to explain painful experiences by looking for a biological cause. While ruling out any medical concerns can be helpful, it can feel invalidating if no conclusive or definitive explanations are found and pain is often treated and spoken about differently when psychological reasons are suggested - “it's all in my head.”

For evolutionary reasons and survival our brain will be especially geared towards prioritising protection of our reproductive organs.

We and/or our partners would benefit from more sexual health literacy to understand normal sexual functioning. Sex does not need to be painful for example or penetrative sex is not the only or ideal way of engaging in sex.

What can help build more safety in sexual situations?

Understand the factors that contribute to your pain.

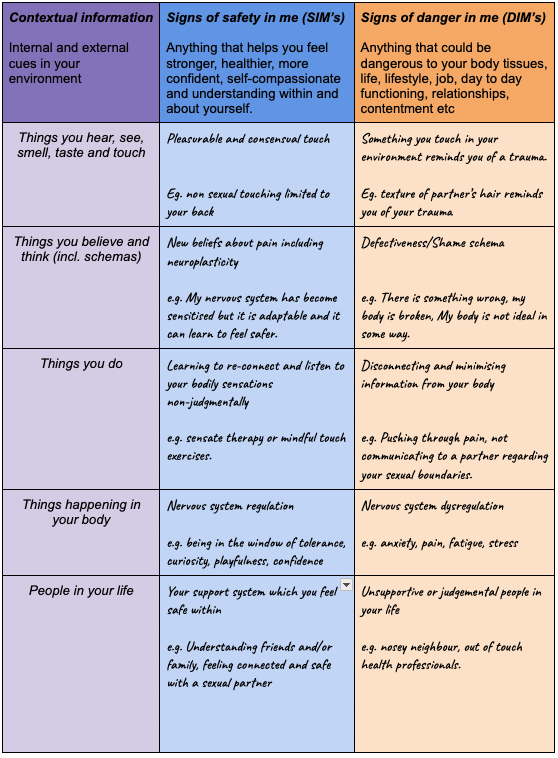

There is a helpful exercise from the chronic pain field that we can use to help us piece all the factors together. It is the Protectometer and consists of identifying Signs of Danger in me (DIM’s) and of Safety in me (SIM’s). Below are some examples. I have added Past experiences but as a whole they can represent the general background information guiding your brain’s pain response but also help you name and understand the specific factors at play during painful sex as they may not all be active at once.

Adapted from Protectometer, Moseley & Butler, 2017

The aim is to increase understanding and awareness of these factors, to decrease the number of DIM’s we experience and increase SIM’s. As a tip, some DIMs can be SIMs in different contexts such as the example of places you go above. Some DIMs can be changed into SIMs, for example through therapies that support the development of new and helpful beliefs.

You can try identifying what your DIMs and SIMs might be with this downloadable template here.

Therapeutic techniques:

EMDR and other trauma processing approaches. Especially where there has been a history of sexual trauma or traumatic experiences such as medical trauma that impact in some fashion the quality and experience of sex. Not only can this help reduce the impact of traumas on our day to day experiences and mood and reduce trauma related symptoms such as hypervigilance but also allow for the development of more adaptive ways of thinking about ourselves and the world. For example, we might move away from shame and self-blame towards feeling greater self-compassion or even agency and confidence to advocate for our needs and rights going forward.

Mindfulness and sensate approaches. Paying attention with curiosity rather than judgement and fear can disrupt the pain-fear cycle that many people experience with sexual pain, deactivate the brain's threat response and allow your brain to more accurately appraise the safety of the situation; that the sensations are not dangerous and you are safe. The more you are able to practise viewing pain without judgement the more evidence will build up for your brain to start anticipating and thinking about sex differently as more neutral and as you feel more able to safely stay connected to your body you may invite some more pleasant sensations in further reinforcing a growing feeling of safety.

Chronic Pain management is a team sport. With sexual pain too, having a multidisciplinary team to address different contributors to your pain is good practice. This can include pelvic floor physiotherapy, gynaecology, GP with experience in sexual health, dermatologist, endocrinologist…

Interoceptive and embodiment focused approaches to build awareness of how trauma, or historical, relational and contextual experiences show up for you in sex.

Relationship therapy, if concurrent concerns have contributed to either the onset or maintenance of your sexual pain, for example infidelity.

Self-compassion approaches to non-judgmentally hold and work with your nervous system and away from a mechanistic perspective on your body as broken.

Schema therapy/IFS/EFT etc to address longstanding patterns of cognitions, emotions and behaviours which may impact the meaning and coping responses to pain for you.

If some of your anxiety is related to not understanding your own sexual likes and dislikes, a helpful resource to learn more is the website OMGYES. It contains a series of videos that demonstrate different types of touch, including techniques labelled “edging,” “layering” and “orbiting.” This can provide a guide to help you explore your body and start to experience your body as a place of curiosity and pleasure. It can also support your sexual communication to a partner.

Enlist the support of a trusted partner in re-building safety with sex. Healing from sexual pain is both individual but also can’t take place in a vacuum and being able to share and practice strategies together will also be an important part of the process. Good communication is incredibly valuable for creating safety and is a good example of where the process can be shared. Sensate therapy can be individual but also very beneficial to engage in with a partner to become more mindful, embodied and desensitise a fear association between sex and pain.

Your pain is real and valid! Understanding the way our brains shape our experience of pain is the first step in healing. The act of naming something and understanding its function can start to take away some of the fear of the pain and judgement about ourselves and our body.

Final thoughts :

Our nervous systems are incredibly adaptable at any age, older or younger, and we can work towards having more of a positive and pleasurable relationship with sex again. Always check with a trusted medical professional, but understanding your pain is multifactorial, influenced by many factors in your life context is critical to healing. It will take some time retraining your brain to trust that it can be safe again, it wants to protect you and what is important to you, sometimes it does this too well so finding a balance between not disregarding its fears and warnings but also doing enough to create new experiences which challenge its existing perspective will be helpful to keep in mind. Having a knowledgeable professional who also provides a secure space to collaborate on this can also make a difference and even help you feel less alone.

Resources:

Why pelvic pain hurts, by Adriaan Louw, Sandra Hilton and Carolyn Vandyken.

Pain and perception, by Daniel Harvie & Lorimer Moseley

The Explain pain handbook: Protectometer by Lorimer Moseley & David Butler

This blog post is a brief exploration of this topic and does not replace therapy. At SHIPS, we have practitioners that are knowledgeable and skilled in a variety of areas including sex therapy, relationships and more.

If you may benefit from some support, please check out our website resources, or contact us.

We are also always happy to hear feedback about our blog articles. If you would like to share your experience or feel we may have missed something on this topic, please contact us to let us know.

How can SHIPS help you?

AUTHOR

Michelle Pangallo

Counselling Psychologist